27 Jun building A workers network against the supply chains of war

Two recent trade union meetings, one held in Genoa in May, the other in Livorno in early June, have slightly changed the working perspective of the Weapon Watch observatory.

Born in early 2020 to monitor the movement of weapons through European ports, WW has been clear from the outset who are the recipients of the information it is able to collect. Of course, it addresses the pacifist and anti-militarist movements, the NGOs most sensitive to the humanitarian and environmental consequences of wars, the investigative journalists of the international media. However, its data and investigations are primarily intended for workers who manufacture and those who handle weapons, that is, who participate in military logistic chains and who, despite the increasingly heavy blackmail of companies and governments, do not adhere and do not want to close their eyes.

WW aims to stimulate their “objection”, which can be ethical, religious, libertarian, civic (see article 11 of the Italian Constitution) and also economic (governments buy weapons only by subtracting resources from social, health, education and environmental spending etc.) but which in any case converges towards historical observation: after the Second World War, neither a country nor a military alliance has been able to win a war anymore. As the case of Afghanistan amply demonstrates, up to the disastrous withdrawal in progress, contemporary wars are fought without the intention of winning them, let alone ending them. This would be like founding a company that gives huge profits to those who lead it and then closing it because its employees do not make a living from it or get sick from working on it or undergo progressive dehumanization.

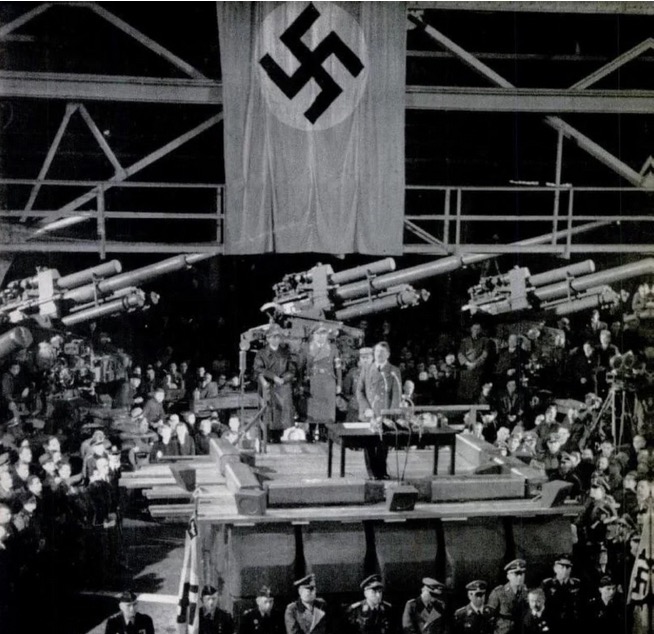

War – like environmental pollution or slavery – is now meaningless. It is not justifiable even from the capitalist point of view, if not from the “disaster” point of view of which Naomi Klein spoke. War grabs enormous resources and largely destroys them, or directs them to continually renew equipment that will hopefully never be used (think of nuclear weapons) or will be used above all against unarmed civilians (think of the so-called “conventional wars” in course). Rich and stable societies, such as those in Europe and North America, are brought to their knees by powerful migratory currents, the effect of the wars that their governments fuel by supplying weapons. Governments themselves are competing to provide absolute and tribal monarchies with the best of the technologies of death. Western weapons will soon be used to impose on western countries the consumption of oil, the catastrophic effects of which we are beginning to assess. «The guns you are building – Bertolt Brecht wrote to the German workers – are already aimed at you.»

Rheinmetall is one of the large European companies that supplies arms to the absolute monarchies of the Gulf, and also has branches in Italy.

In some places in the world, small avant-garde workers are trying to point out the senselessness of wars and indicate the “names” not only of the companies and governments that control the arms trade, but also of the intermediaries (ship-owners, brokers, freight forwarders, etc.) who pretend not to know where the weapons they help carry go and what they will be used for. They have done so above all in ports and logistics platforms, where “goods” are once again the physical object of exchange, no longer hidden in the digital universe through which information and money run dematerialized. They did so with demonstrative actions of clear nonviolent tradition, with pickets and strikes against goods destined for the massacres, against containers full of bombs and bullets, against shipping companies born to serve militarized supply chains.

It is no coincidence that these struggles were first of all against two logistic chains supporting the global international order. Namely those that keep the “besieged citadels” of Israel and Saudi Arabia with the Emirates, countries now united by mutual ties and declared intentions and they have internal elements of similarity (theocratic-authoritarian imprint of the political classes, military-industrial apparatuses worthy of the International Criminal Court, socio-economic discrimination based on gender and ethnic origin). The Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the Shiite-Sunni conflict basically reflect the same abyss, from which the current wars and probably future wars were born in the twentieth century.

However, in this rather unpopular landscape, positive elements are gaining ground, a reaction to the inevitability of inhuman wars and at the same time collective awareness of: the interconnection between the issues of peace, of a sustainable environment, of more free movement of men and less free movement of capital, and therefore finally of a non-identity culture that allows this collective consciousness to open up to confrontation, to go beyond differences and indeed to recognize them as the first step in resolving conflicts.

These are positive elements that WW also finds from his peculiar observation point. The network between the ports that act against war (in Italy Genoa, Livorno, Ravenna for now) is being formed. It is connecting to the European realities (starting with Bilbao) and the Atlantic (a few days ago also the Californian port of Oakland blocked goods bound for Israel). The initiative underway in Hamburg, where a popular referendum is proposed to exclude armaments from the city’s port traffic, can also be repeated in other European port cities. In addition, the Swiss popular initiatives – a referendum rejected in November 2020 for the ban on financing war material producers, and one to be held in 2021 against arms exports to countries in civil war – show us a viable path also in Italy, a country large producer in which exporting companies have multiplied their profits even in times of pandemics.

Here lies a major contradiction. On the one hand, the companies that produce for defense depend on government military budgets, of which strong growth is expected despite the Coronavirus having clearly shown the serious flaws in health systems. This being the case even in the richest and most equipped countries. On the other hand, the competition between the major national industries takes place on a global market, where the buyers are developing countries often without transparent controls or already involved in criminal wars, often against their own peoples. Covered by this mighty mix of protectionism and liberalism, defense industries and services are growing in total opacity, claiming their “paramount importance” at home and abroad, sharing the richest markets with bribes, in league with corrupt local elites. Wars raise prices, peace depresses their business.

Making these power mechanisms explicit contributes to limiting them. What a small vanguard of workers is doing in Italian ports, however immediately targeted by police repression, brings out what humiliates many other workers, against whom wealthy bosses with thriving company budgets turn the responsibility for the protests against wars. Moreover, a part – numerically limited but very profitable and protected – of jobs actually depends on wars and collective insecurity: this too is becoming increasingly evident. If it does not seem possible to involve these “bloody workers” in a frank debate on sustainability and the conversion of their workplace, it should also be noted that the method and the trade union organization are regaining ground even where they were in crisis or non-existent. Both American and Italian experiences indicate that it is precisely the confrontation on “political” issues – gender issues, the environment, wars – that contributes to the creation of informal discussion groups, which are then often extended to include workplace conditions and forms embryonic resistance-struggle. It is also clear that the persistent protest of Italian dockers against wars has brought them the sympathy and support of youth sectors, political and religious organizations, local administrators, together with a strong international media attention that will be difficult to ignore even when union delegates go to check job security on the dock or discuss jobs and wages with employers.

THE WEAPON WATCH

THE WEAPON WATCH