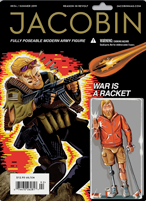

25 Giu We Won’t Load Your Ships of Death

An interview with Giacomo Marchetti

[articolo pubblicato su Jacobin Magazine]

Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen relies on lucrative weapons deals with the West. But the arms shipments can’t happen if dockers refuse to load the ships — and in France and Italy, they’ve already taken strike action to stop the Saudi war machine.

Since March 2015, Saudi Arabia’s deadly airstrikes have visited destruction on the people of Yemen, killing almost 18,000 and leaving most of the population at near-starvation levels. The Saudi bombing campaign is intended to suppress the Houthi rebels who have taken over the capital Sana’a and much of the west of the country, but it is also a proxy for a wider regional conflict with Iran.

Thus far, the Saudi tyrants in Riyadh have been able to count on Western backing — and weapons. Yet as scrutiny of their war crimes intensifies, the edifice of support is beginning to crack. On June 20 the Senate voted to block Donald Trump’s plans for $8 billion of weapons shipments, just hours after a ruling by the UK Court of Appeal forced Theresa May’s government to suspend arms sales to Riyadh.

The workers in all three ports made clear that they weren’t willing to be mere cogs in Saudi Arabia’s war machine, refusing point blank to load what they called the “ships of death.” Indeed, when fresh news spread that another ship called the Bahri Yazan was going to dock in Genoa last Thursday, workers and antiwar activists in the northwest Italian city were quick to mobilize, with protests and a further strike call.

Yet the first resistance came elsewhere — from the workers meant to make the arms shipments happen. On May 10, the Bahri Yanbu was unable to dock in Le Havre as workers refused to accept the Saudi vessel, and ten days later their counterparts in Genoa went on strike rather than load the ship. On May 28 members of the CGT union in Marseille similarly boycotted a Canadian weapons cargo headed for Saudi Arabia on the Bahri Tabuk.

The result was again humiliation for the Saudis, as port authorities were forced to guarantee that the workers would not have to load weapons onto the ship. Yet the fight to cut off supplies to the Saudi war machine is far from over. Jacobin’s David Broder spoke to one of the Genoa dockers, Giacomo Marchetti, about his colleagues’ action, the political response, and how workers can take direct action against war and militarism.

DB: On May 20 the Genoa dockers refused to load weapons onto the Bahri Yanbu, showing that you were unwilling to help Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen. Where did the decision to take this action come from, and what do you think it achieved?

GM: The traffic of arms through the port was nothing new. It was something that our Autonomous Port Workers’ Collective (CALP) had publicly denounced on several occasions. But this didn’t receive any particular media attention, or indeed an adequate response from political or trade-union organizations.

Like many aspects of what goes on in the docks, this arms trafficking was a “taboo.” We see the same thing with the shipments of other dangerous goods, and the situation of insecurity the workers are forced to operate within. It’s all part of a kind of pact (also in part including the unions) which sacrifices everything else on the altar of the maritime business, on the basis of a sort of omertà. You could say the same of the long-standing failure to plan any road-based alternative to the heavy traffic over the Ponte Morandi (the bridge in Genoa that collapsed on August 14, 2018, killing forty-three people).

But a series of factors — firstly the blockade carried out by port workers in Le Havre and a positive response among activists in Genoa — led to a change of pace. Under strong pressure from the workers’ delegates, as the Bahri Yanbu was approaching Genoa the FILT-CGIL union called a strike. A blockade was called the day that the main shipment was meant to be loaded. A group of workers thus gave their own kind of “welcome” to the Saudi vessel.

Another important factor in getting people to mobilize for the first blockade was the “pre-electoral” climate (it took place just days before the European elections) as well as the clear position taken by a vast array of associations, including ones of a Catholic orientation.

That said, ultimately it was a group of “inglorious bastards” among the dockers, and their determination to ramp things up a notch and create a precedent, that proved decisive to making the strike call happen.

As for what we’ve succeeded in doing, we’ve made people start talking about the long-overlooked conflict in Yemen. We’ve made them talk about the traffic of Western-made weapons that feed wars causing vast humanitarian disasters. And we’ve reasserted collective action as a tool for addressing the problems in front of us — including in response to issues whose importance extends beyond our own workplaces.

This was a beginning. And after our action on May 20, eight days later the dockers in Marseilles did the same.

DB: How did the Port Authority and the local prefect respond to your action? On June 19 another Saudi ship came to Genoa. Can you be sure there won’t be further efforts to use the port to send arms for Saudi Arabia to use in the Yemen conflict?

GM: We know that the traffic of weapons will, indeed, continue. It’s our responsibility to monitor it, point it out where it’s happening, and take the necessary action in response.

We’ve long noted a certain nervousness on the other side [i.e., the Port Authority], after they initially tried to deny some undeniable truths. They’ve been evasive about the nature of the cargo that was meant to be loaded, its final destination or how it was going to be used. Here, we are talking about military-spec engine-generators that have received a kind of authorization necessary for the traffic of weapons destined for the Saudi Guard, a military corps deployed on the Yemeni front with three brigades totaling 30,000 men…

Ultimately the maritime agency, acting under the indications of the arms manufacturer Teknel, issued a communication to the Port Authority saying it would not load the weapons. This was the result of pressure that produced an information counteroffensive over the previous week — which also had an echo in the wider media — but also the protest outside the Port Authority on Wednesday, June 19, and plans for a strike and a dawn picket at the main entry to the port the following day. Yet once the official communication came in on the Wednesday evening, and a delegation had been received by the Port Authority, we decided together with the people present at the protest that our demands had been satisfied, even as we continued to monitor the situation.

DB: How are you organized? What other movements are involved in the protests? Is the CALP port workers’ collective part of the trade union?

GM: The CALP isn’t a trade union or part of it, but a body made up of workers, delegates, and other comrades who contribute at different levels. Over the years it has become a well-regarded point of reference both within and outside the docks. It has established a relationship of trust in practice, especially through the central idea of “working-class combat” — the readiness of some of the workers (even if a minority) to enter into confrontations on key questions, which aren’t necessarily linked to the port itself. It makes its voice heard in a way that some might consider a bit “pyrotechnic” or overly direct. But as in this case, that’s often an effective way of doing things!

DB: Of course, there’s historical precedents for this kind of action — take the London dockers who in 1920 refused to load the munitions that were meant for the war against the young USSR. Do you have similar traditions in Genoa

GM: The port of Genoa has always been at the center of solidarity actions against imperialist war — from the war in Vietnam to the war in Iraq, not to mention the resistance against Pinochet in Chile.

Our action followed in this same internationalist vein. We took this action even though conditions are difficult given the wider balance of class forces and the difficulty of asserting any narrative in today’s Italy that goes beyond setting the very-worst-off against the next-worst-off, for instance dividing the Italian poor from migrants.

One of our slogans is “close the ports to weapons and open them up to people,” together with “an injury to one is an injury to all.” That doesn’t just concern the ports, or even Italy. We were also in solidarity with Donbass, Catalonia, and Rojava. But this time the action was much more effective and visible. That’s what troubles the “party of war” stretching from the neoliberal Democratic Party to the fascist scum. The fact that a part of the working class in Italy and France conducted this internationalist action should make people reflect on the falseness of certain narratives about what workers think, with which some people meant to be on the Left have intoxicated the public debate.

We’ll continue to fight on the questions this dispute has raised, deepening our analysis and developing our means of action. We’ll do so thanks to the aid of those outside Genoa working on the same issues. We have made a crack in the war machine — now we need to open it up further, for those who make war should never be left at peace.

THE WEAPON WATCH

THE WEAPON WATCH